Dining in the Dark

In Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost town, our social calendar is defined by the moveable feasts of welcomes and goodbyes. No one comes to Svalbard, a visa-free Norwegian archipelago, to settle permanently. Very few babies have been born here — pregnant women are sent to a hospital on the mainland ahead of their due dates — and once people can no longer support themselves (because of unemployment or age, for example) they are legally required to leave. That gives the connections that are made here a precious quality, as ephemeral as the ice caves that form and disintegrate in the glaciers each year.

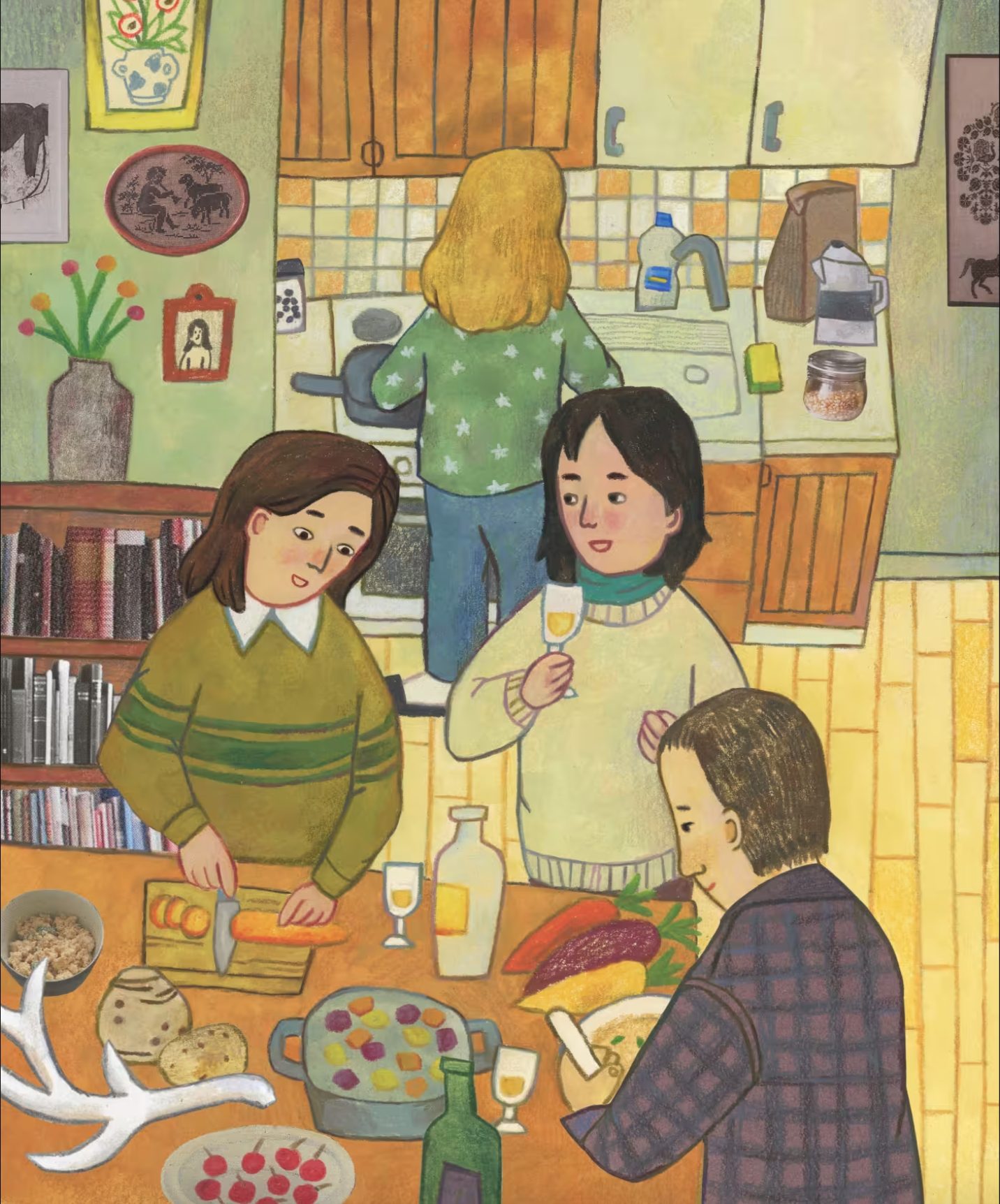

To strengthen those ties — to debut newcomers, bid farewell to old friends — we hold dinner parties. Though much has been written about the hidden paladares of Havana, the seven-course cenone of Italy, I doubt there are many cities in the world with a dinner scene as thriving and vital as that in Longyearbyen. These private gatherings are especially important in the polar night that lasts from mid-November to the end of January, when home-cooked meals and close friendship provide the light and warmth we need to get through the long months without the sun. The young town has just a handful of restaurants, no locally grown produce and no distinct local specialities, so community and cuisine start in the kitchen.

For years, the most sought-after dinner invitation in Longyearbyen was arguably Sjøområdets Folkekjøkken (roughly translated as “the people’s kitchen by the sea”), founded by friends Sally Hovelsø and Theres Arulf in 2012. This wintertime supperclub disappeared as the original group behind it dwindled. But last November the first Folkekjøkken in nearly seven years was staged.

The light was low when I arrived for Folkekjøkken, hosted at Dutch silversmith Marina van Dijk’s workshop. The sun had set for the last time a week earlier and would not return for nearly four months. But Svalbardians have learnt to round down the corners of the dark until it fits them, soft and familiar.

Candles flickered on the worn wooden table that ran the length of the loft above the workshop. Among those who sat down were a sculptor who moonlights as a nature guide and a skipper who writes French poetry. Settled for coal mining, Svalbard’s main trade is now in experiences — memories of a changing Arctic to contemplate after the glaciers are gone. Those who thrive here can make a living off these memories. I sat beside Elizabeth Bourne, the American director of the artists and writers residency where I spent my first month in Longyearbyen, and looked at photos of her recent tall ship trip around the archipelago. After the residency, I’d decided to defer my graduate school plans to spend at least a year writing in and about Svalbard.

When all the mismatched chairs were occupied, Hovelsø began depositing restaurant-grade vessels of food between the dripping candles. There were pots of tabbouleh, a sheet pan of focaccia pockmarked with olives, eight-quart steel mixing bowls filled to the brim with hummus and baba ganoush. Then falafel emerged from a vat of oil on the nearby electric stove.

“How did you make all this?” I asked Hovelsø. I had attempted most of these dishes before, and I knew each takes hours of work. I was also impressed by her creativity with the limited ingredients available here; Longyearbyen has one supermarket, a carbon copy of the Co-ops in mainland Norway, plus a small Thai store. “I like it,” she said simply. “It brings people together.”

It must have felt like the right time to bring people together. Longyearbyen had changed since the last Folkekjøkken in 2016. During the pandemic, many foreign tourism and hospitality workers lost their jobs and housing (apartments are usually tied to employment in Svalbard), shifting the demographics of the town. Most of those who remained lost their voting rights in 2022, when a new electoral law barred anyone who had not lived in mainland Norway for at least three years from participating in local elections. (Though Svalbard is under Norwegian sovereignty, foreigners can live and work here without applying for Norwegian residency because of the archipelago’s visa-free status.)

Hovelsø, who is Danish, was one of dozens of people who lost her right to vote in the only town she called home. Feeling betrayed, she organised protests against the law, one of which took place at the airport during a visit from Norwegian prime minister Jonas Gahr Støre. The demonstrators wore tape across their mouths and T-shirts printed with the words “Unwanted Foreigner”.

Many of the people at the dinner had participated in the protests. As they worked through the bottles of wine they had brought along, they shared grievances unique to living as immigrants in a visa-free zone. “Most of us here are unwanted foreigners,” said Bourne, looking around the room. “I don’t feel unwanted,” I proffered. The tide of conversation swallowed up this awkward remark like a pebble. But it was true; I’d found the people with whom I wanted to descend into the polar night.

A month later, after the Christmas tree went up in the town square and the ruins of the old coal mine were decorated to look like Santa’s workshop, I was invited to the home of Dutch artist Sarah Gerats to eat a reindeer. It was the peak of polar night in Longyearbyen — not a fringe of twilight on the horizon — and Gerats had just returned from nearly three weeks working as a field assistant at Tarandus, a research station deep in the tundra, part of a 30-year observational study of the Svalbard reindeer subspecies.

Life at Tarandus is dictated by the habits of the animals. The researchers track reindeer via GPS collars, watch their foraging behaviours and take samples of their droppings, to understand how they are responding to climate change. The American biologist who ran the foraging study, Sam Dwinnell, was also at Gerats’ converted boathouse, as was her second field assistant, Maggie Coblentz, a Canadian-American artist and designer who swayed to electronic music as she sliced a swede. They moved together with the easy rapport of those who have grown used to spending time together in confined spaces. We were marking their return, but also their impending departure. Dwinnell and Coblentz would soon be leaving the island to work on other projects.

“Sometimes here, you have this built-up longing to be together that can be quite sudden, unexpected and explosive at times,” Gerats told me later. Like Hovelsø, she has lived in Longyearbyen for 12 years, interspersed with stints working on ships in the Antarctic. “That night in December, everyone had some build-up. From the moment that everyone came in, it was clear that it had to explode in a way.”

The atmosphere in her loft was heavy with this feeling, and with the gamey steam eking from a red enamel pot large enough to boil a piglet whole. We were making pinnekjøtt, a festive Norwegian dish usually involving lamb or mutton ribs that are salted, dried and then steamed in their own juices. This one was made with a Svalbard reindeer, killed by poet and children’s librarian Eirik Bø. (Permanent residents of Svalbard are allowed to bag one reindeer per season after passing a few qualifying examinations, such as a big game shooting proficiency test.)

Bø, who moved to Longyearbyen from Oslo last spring, may not strike one as an archetypal Arctic hunter. A baby-faced 29-year-old, he is still sometimes asked for ID at bars. At the end of one evening out I found him in a corner watching videos of ducks wearing flowers as hats. The reindeer was one of the first mammals he’d ever killed, other than hares on boyhood trips in mainland Norway’s gentle forests. His first hare brought him to tears; the reindeer did not, though he admitted that he felt for the animal as it coughed up its lungs.

But Dwinnell, who has spent more time with the reindeer than any of us, has no qualms about eating the animal. “Whether you’re hunting, researching, photographing or even just really sitting and observing these animals, undoubtedly, you make a connection,” she said. “I enjoy eating the meat from the animals that I’ve hunted, or eating the meat from the animals that friends of mine have hunted, because I know there is this connection.”

By the time we’d finished the crémant and opened a few more bottles, the reindeer flesh had reached melting tenderness. We spooned it, with its juices, on to plates with buttery puréed rutabaga, roast potatoes and vossakorv, a smoked sausage. Our table was low, our seats cushions. We squatted, sat cross-legged or knelt seiza-style, depending on flexibility. Gerats had suspended a moon-white fragment of reindeer antler from a string above the table.

Svalbard reindeer, evolved to fast through the famines of winter, have the highest body fat percentage of any deer species — up to 40 per cent at the end of summer. Ours, cut down at the zenith of its pre-winter bacchanal, bloomed with richness, its muscles as marbled as Wagyu. We consumed the bounty it had stored for itself, slicing through the fat with sips of akevitt. We picked up the bones and sucked the marrow from the spongy pores. Perhaps it is the caraway and dill in the liquor — the rich meat requires an ample dose — but I could swear I caught the scent of the summer tundra.

Within weeks, most of the people in that room had scattered to other parts of the world. During the remaining months of night, left behind in the dwindling town with the reindeer and a few other non-migratory species, I often thought of that dinner and wondered if there would ever be a reprise.

“Here, I think you can never go back to something,” Gerats warned me when I met her for coffee in February. We were two of the few people from that room left in Longyearbyen. “You can never expect the same thing again.”

“But it’ll be nice,” she said, smiling, as we planned for the coming spring.

The sun reveals itself striptease-slowly in Svalbard, hinting at its presence long before it finally climbs over the horizon. It begins with a ribbon of twilight around noon, so faint you could mistake it for a retinal flaw, that widens daily in space and time. With it comes a kind of melancholy, like the bittersweetness of daybreak after a joyous night out.

Longyearbyen is walled in by mountains, so it takes especially long for the sun to reach our patch of sky. We spent every weekend in blue February snowmobiling through the moonlike valleys in search of it. One Sunday I joined a faction of government workers on an excursion to Reindalen, the valley where our reindeer died. We climbed a slope, and I wondered for an instant why the few centimetres of exposed skin below my goggles felt as warm as if kissed. It was the sunshine, which I had not seen in nearly four months.

We parked our snowmobiles on the hill and brought out thermoses of coffee and Tupperwares of cake. Leonard Snoeks, the partner of a city planner, turned on the speaker he had strapped behind his seat, the size of an ’80s boombox. The first song he played was “Here Comes the Sun”; the rest was dance music so we could bounce and sway in our puffy scooter suits. Everyone looked beautiful with the pink light rouging their snow-nipped cheeks.

Suddenly, the sun returned to Longyearbyen. On March 8, the town gathered on a hillside to welcome it. “Sun, sun, come again, the sun is my best friend,” the children chanted in Norwegian, wearing corona hats and circles of yellow paint on their cheeks like Burmese thanaka. There were less than two months remaining until the endless daylight of Arctic summer.

After sunrise, it was the ebbing nights that became precious. My friends (I can call them that now) and I gathered for the last supper of the dark. Maggie Coblentz was host this time, fresh from her field excursion in Lanzarote with a deep tan and a lengthened gaze. Sam Dwinnell was back from a months-long stint in the labs at her mainland university. Nearly everyone from the reindeer party was together again, with new friends besides. But I remembered what Gerats told me: “You can never go back.”

For the first course, the table was spread with simulated skin: squares of silicone roughly the size and texture of cheese singles. Instead of forks and knives, we had needles; thimblefuls of ink sat beside our wine glasses. Coblentz’s friend Nancy Valladares, an artist and academic visiting from New York, was teaching us how to do stick-and-poke tattoos — a high-stakes version of a paint-and-sip.

When we’d tortured our silicone skin enough, we cleared the squares away and replaced them with pizza. I nibbled on a mushroom slice and glanced at the arms of my fellow guests. Everyone wore a little gallery there except me.

Valladares said that there was no pressure to do real tattoos, but the others didn’t hesitate. Lena von Goedeke, an artist who splits her time between Longyearbyen and Berlin, marked Dwinnell’s wiry forearm with four intersecting lines: the radio telemetry antenna she uses to track reindeer across the tundra.

I contemplated the doodles on my silicone sheet. Along with a few dogs and cats, I’d written my name in the runic alphabet, one of the tangents I’d wandered down during the polar night. The first letter, jera, is an ancestor of the English word year. In runic divination, it represents the cyclical nature of life, the harvests that come in their season and fade away again. I drew the rune on the soft flesh between the first two metatarsals on my right foot. The needle hurt less than I expected — about the same as plucking an eyebrow hair, but in reverse. The two lines, bent towards each other like lovers, came out straight and clear.

After remaining diligently sober through the tattooing, we toasted the night with mango-scented mezcal from Mexico, which Valladares had picked up in New York before her flight to Norway — about as convoluted a journey as any of the rest of us took to Svalbard. Most of the people in the room would leave Svalbard within a month; some had no plans to return. My promised year was more than halfway gone. The temporary quality of life and human connections is clearer here than anywhere else. But the rune will stay with me, a reminder of the last supper and the long night it closed.

A version of this article appeared in the Financial Times Weekend Magazine, April 20 2024.